Natural Hones/Waterstones

There are a large number of these available, some of questionable value to the open razor owner, some capable of superb results and others remarkably hyped-up – particularly on razor forums – beyond all reasonable measure. My advice to somebody beginning to hone is to avoid these at first and get a set of man-made hones. That way you will understand the grit rating of each hone and be able to place it in a honing progression. Natural hones, of course, cannot be assigned a grit rating. We attach an estimate of grit value to them as a means of describing them, but this can vary, sometimes quite wildly, even for natural hones of the same type. The British Isles sport a fair number of natural sharpening stones suitable for our uses. They range from low grit to finishing hones. A partial, though by no means comprehensive list follows.

Dalmore Yellow

Quite a coarse hone from Scotland, approx. 2000 – 3000 grit. Usually quite slow in use, although – being a natural stone – it is subject to variations. I have had one reasonably fast one. A common complaint is that they are “sandy” in texture and small grains are apt to come loose and spoil the work. Not really suitable for razors.

Dalmore Blue

From Scotland again, approx 4000 grit, perhaps peaking at 5000. Medium to slow speed, useful for refining a bevel but not really fast enough for setting one. Originally hones were taken from Craiksdale Quarry but were later transported to the Water of Ayr & Tam O’Shanter Honeworks at Stair for sale. The Dalmore Blue was sold as a ‘medium’ grit hone, followed in terms of increasing fineness by the Tam O’Shanter (ordinary and fine) and the Water of Ayr (very fine). They are mostly not blue in colour, having a greyish/greenish sort of colour, perhaps with a hint of blue. Most noted for the lovely swirls of colour in them, most are quite highly patterned.

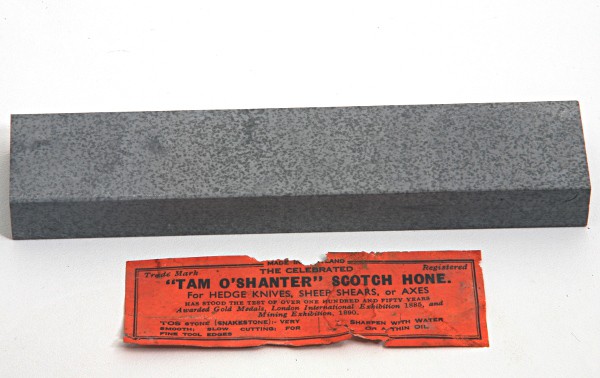

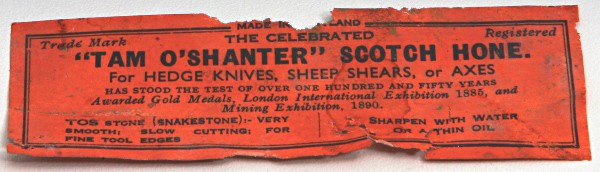

Tam O’Shanter

Another from Scotland, approx 8000 grit (I have had white ones that were higher), although some people rate them as low as 6000 grit – again, they are natural stones so there is no conformity to them. Lovely speckled pattern. Reasonably fast in use and considered by some as a finishing stone and for removing micro-nicks. If going on to a finer hone it is said to impart a smooth quality to the edge. It has another attractive quality too – it is one of the few hones that can be used effectively on razors that are prone to micro-chipping during honing. If used with a slurry (made by rubbing a slurry-stone over the surface) it cuts a lot faster.

An interesting point is that the Tam O’Shanter was sold in two varieties: one for cabinet makers, etc, and a “fine” version for razors. The distinction is made on the label and on the original box, so it is not seen that often. The one fine version that I have been able to verify had a grit equivalence higher than my 8,000 grit stone. There is another variant that does not look like the other TOS stones – the white Tam O’Shanter. This one was sold for producing “very fine edges” and is finer again than the fine Tam O’Shanter mentioned above.

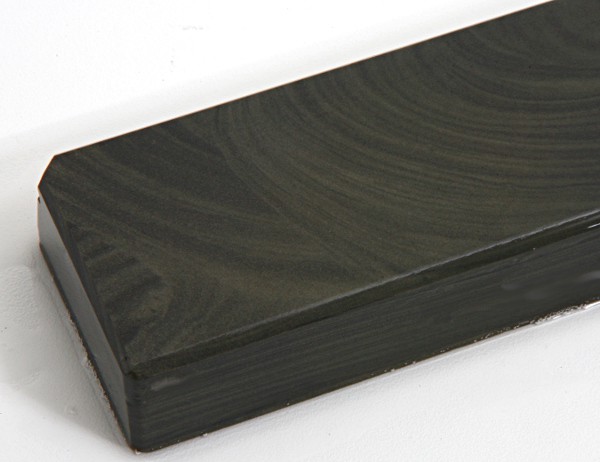

Below is a picture of a small white Tam O’Shanter followed by a picture of the label from another white Tam O’Shanter:

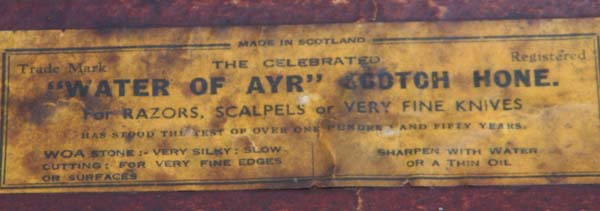

Water of Ayr

Another offering from Scotland. The Tam O’Shanter was originally listed as “fine” and the Water of Ayr as “very fine.” Historically, the Tam O’Shanter and Water of Ayr stones, although quite different, were lumped together and known as “Scottish hone” or “snake stone” so today there is still a little confusion so make sure of what you are buying – only the Tam is very speckled. The Water of Ayr gives a very fine edge and is in the region of 9,000 – 11,000 grit size. It is identified by the presence of sporadic dark dots, sometimes quite large, sometimes joined together with faint lines

Belgian Blue Stone (BBW)

This stone occurs in the Ardennes and is a garnet-rich hone of around 4000 grit equivalent. Most of these hones give excellent polishing results, removing the lines left by coarser hones, but they are generally regarded as slow – too slow for bevel formation. The usual caveat applies – it is a natural stone, and different samples may display different characteristics. For instance, I have a BBW hand-selected by the mine owner – it is midway between a BBW and a yellow coticule in garnet size and cutting speed, and I would rate it somewhere above 5000 grit. Historically, the BBW was thought of as insignificant from a honing point of view and was used as a backing for the yellow coticule because it was regarded as cheap and disposable (natural slate is used now). The BBW works with a slurry. It does not need to be soaked before use.

Belgian Yellow Coticule

These are remarkably versatile garnet-rich stones, found in the same place as the BBW. When soft, they can be used to cut metal quite fast with a creamy slurry, and do the work of 6000 – 8000 grit hones. Reducing the consistency of the slurry slows the cutting rate down, but makes the stone cut like a finer grit. Using just water provides the keenest edge (some say using it dry gives the keenest edge). Harder yellow coticules are not so good as cutters and are mainly intended to be final polishing hones. A conservative estimate of grit size would be around 10,000. The yellow coticule has long been prized as a honing stone – the Romans made much of them when they conquered the area. Devotees say they give a much smoother shave than other hones, due to the shape of the micro-garnets which smooth the edge. The older stones are said to be the best – certainly, one vintage coticule I owned was a superb finisher. Sometimes they are available as a combination stone, being bonded to a piece of BBW instead of slate (see above: this was a matter of convenience in the past, but a selling point now). The stone does not have to be soaked before use. Generally, the softer the hone the more ‘cutting’ speed/power but the edge is markedly softer, the harder the stone the less cutting action, but the edge is finer. If you get one that is a compromise, then that is just what you get – a so-so cutter and a so-so finisher.

Hybrid or Les Latneuses Coticule.

This is an odd beast. It is not a combination coticule in the strict sense of the word as it is from a layer among other cuticle layers. One side looks fairly conventional, the other has a strange marbled, glassy look to it. The conventional side gives a very good edge – it is hard but quite fast. The other side is extremely hard and difficult to lap, but it gives a very fine edge indeed. When I got one of these I sold all my other cuticles as I was not satisfied with the mushy (aka soft) edge they gave – this type gives an edge unlike most other cuticles and is a delight to use.

One word of warning, though. These coticules are very expensive indeed in larger sizes, mainly due to their fragile nature. The layers separate very easily, and they are prone to fall to pieces if dropped. They do glue back together rather well, though!